PTSD and Veteran-Related Resources

The following is a list of web-based resources for providers who treat Veterans with PTSD and other trauma-related disorders. These include treatment resources, educational information, helpful provider toolkits, mobile apps, and reimbursement programs. Some are designed to be shared with Veterans and their loved ones, while others are tools and trainings for providers. This list of resources is the end result of Division 56's Task Force on Meeting the Needs of Veterans in the Community. Please download the complete resource guide or browse the various links and other information below.

Veterans Crisis Line: www.veteranscrisisline.net - 800-273-TALK (8255) then press 1; or text 838255. Available to Veterans and their families 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Staffed by VA mental health professionals.

Coaching into Care: www.mirecc.va.gov/coaching - Telephone coaching by licensed clinicians to educate, support, and empower family members and friends who are seeking care or services for a veteran.

National Center for PTSD: www.ptsd.va.gov - Includes many resources to help veterans and their families understand PTSD and PTSD treatment including videos, self-help tools, phone apps, and materials to read.

- PTSD Decision Aid: www.ptsd.va.gov/decisionaid - An online tool that helps veterans learn about evidence-based treatment options.

- Whiteboard Videos: www.ptsd.va.gov/public/materials/videos/whiteboards.asp - A collection of short animated videos about PTSD and effective treatments.

- AboutFace: www.ptsd.va.gov/AboutFace - Brief videos of veterans, providers, and family membersdiscussing PTSD and PTSD treatment.

- PTSD Coach Online: www.ptsd.va.gov/apps/PTSDCoachOnline Self-help tools for managing symptoms and coping with stress; includes coaching videos from therapists.

Find a VA Hospital: www.va.gov/directory/guide/home.asp

Explore All VA Benefits: www.explore.va.gov - Designed as a starting place for anyone looking for information about VA healthcare, disability compensation, employment services, etc.

Make the Connection: www.maketheconnection.net An online resource designed to connect Veterans, their family members and friends, and other supporters with information, resources, and solutions to issues affecting their lives.

PTSD Consultation Program: www.ptsd.va.gov/consult - (PTSDconsult@va.gov or 866-948-7800) Expert clinicians from the National Center for PTSD provide free consultation via email or phone about assessment, diagnosis, treatment, resources, education, and anything else related to treating veterans with PTSD. Free monthly webinar with CEUs.

VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for PTSD: www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/ptsd/ - Reviews the evidence for a variety of treatments for PTSD and makes recommendations about incorporating this information into practice for treating veterans with PTSD. Newly revised in 2017.

National Center for PTSD: www.ptsd.va.gov - VA's Center of Excellence for research and education about trauma and PTSD. The website contains many resources for Veterans, their families, and providers.

- Assessment Overview: www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/overview/index.asp

- Clinician's Guide to Medications for PTSD: www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/treatment/overview/clinicians-guide-to-medications-for- ptsd.asp

- VA PTSD Treatment Programs: www.ptsd.va.gov/public/treatment/therapy-med/va-ptsd-treatment-programs.asp

Information about Military Sexual Trauma: www.mentalhealth.va.gov/msthome.asp

Cogsmart for TBI: www.cogsmart.com - Cognitive Symptom Management and Rehabilitation Therapy is a form of cognitive training to help people improve their skills in prospective memory, attention, learning/memory, and executive functioning. Free manuals and resources available.

PTSD 101 Courses: www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/continuing_ed - Over 40 free online courses from the National Center for PTSD, many with free CEUs. A monthly live webinar is also available.

Center for Deployment Psychology: www.deploymentpsych.org - Resources and a variety of free trainings. Includes a section on military culture (see below).

Military Cultural Competency resources and course: www.deploymentpsych.org/military-culture

PsychArmor Institute: www.psycharmor.org - Free education for providers, employers, caregivers, educators and others. Some with free CEUs.

Prolonged Exposure Therapy on-line training: http://pe.musc.edu - A web-based course from the Medical University of South Carolina.

Cognitive Processing Therapy on-line training: https://cpt.musc.edu - A web-based course from the Medical University of South Carolina.

Eye Movement Desensitization & Reprocessing Therapy training information: www.emdr.com

Star Behavioral Health Providers: www.starproviders.org Training available to providers in selected states for civilians providers who are interested in treating service members and veterans. Providers receive training in military culture and treatment and are listed in a registry of specially trained providers.

VA Campus Toolkit: www.mentalhealth.va.gov/studentveteran - Provides faculty, staff, and administrators resources to support student Veterans.

Veterans Employment Toolkit: www.va.gov/vetsinworkplace - Designed to help employers, managers and supervisors, human resource professionals, and employee assistance program (EAP) providers relate to and support their employees who are Veterans and members of the Reserve and National Guard.

Community Provider Toolkit: www.mentalhealth.va.gov/communityproviders - For mental health providers who treat veterans outside the VA health care system. Resources include information on screening for military service, handouts and trainings to increase knowledge about military culture and mini-clinics focused on relevant aspects of behavioral health and wellness.

Reimbursement for Treating Veterans and Service Members

Becoming a VA Veterans Choice Program Provider: www.va.gov/opa/choiceact/for_providers.asp

Tricare: http://tricare.mil/Providers

NOTE: All of these mobile applications are free downloads to smartphones/tablets using the indicated operating system.

My HealtheVet: Mobile Blue Button for Veterans - https://mobile.va.gov/app/mobile-blue-button (iOS & Android)

Helps veterans manage their health care needs and communicate with their care teams. They can access, print, download and store information from the VA Electronic Health Record (EHR) in a secure, reliable and simple way.

Mental Health Apps

LifeArmor - http://t2health.dcoe.mil/apps/lifearmor (iOS & Android)

Users can browse information on 17 topics, including sleep, depression, relationship issues, and post-traumatic stress. Brief self-assessments help the user measure and track their symptoms, and tools are available to assist with managing specific problems. Videos relevant to each topic provide personal stories from other service members, veterans, and military family members.

PTSD Apps

PTSD Coach - www.ptsd.va.gov/public/materials/apps/PTSDCoach.asp (iOS & Android)

Can help people manage symptoms that often occur after trauma. Features include information on PTSD and treatments, tools for screening and tracking symptoms, tools to handle stress, direct links to support and help.

CPT Coach - www.ptsd.va.gov/public/materials/apps/cpt_mobileapp_public.asp (iOS only)

A treatment-companion app for patients to use with their therapist while in Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT). Includes education about CPT, ability to track PTSD symptoms over time, homework assignments and worksheets, tools to track between-session tasks, and reminders for therapy appointments.

PE Coach - https://www.ptsd.va.gov/public/materials/apps/pecoach_mobileapp-public.asp (iOS & Android)

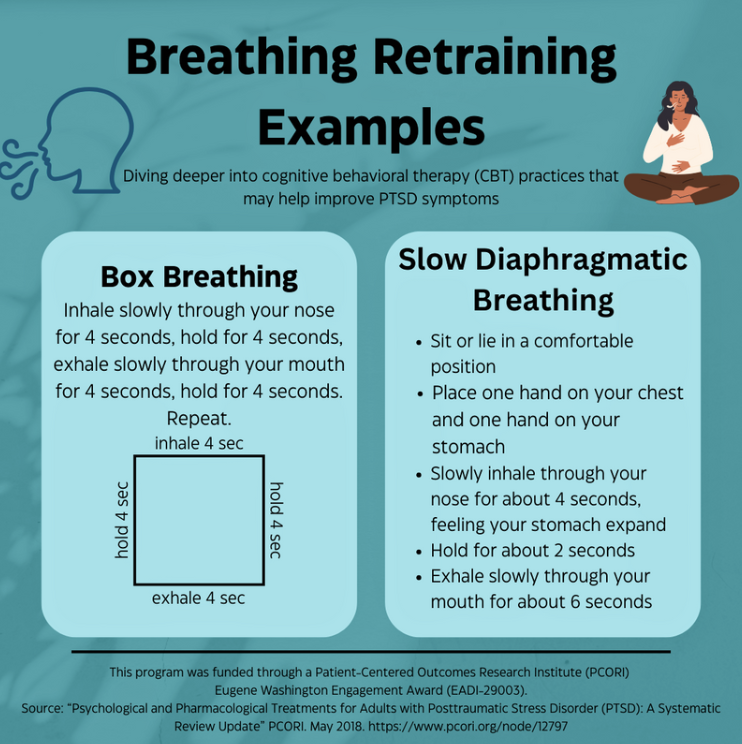

A treatment-companion app for patients to use with their therapist while in Prolonged Exposure (PE) Therapy. Includes education about PE, ability to record PE therapy session, ability to track PTSD symptoms over time, homework assignments and worksheets, tools to track between-session tasks, and reminders to complete homework, and guidance for breathing retraining.

T2 Mood Tracker - http://t2health.dcoe.mil/apps/t2-mood-tracker (iOS & Android)

Allows users to monitor and track emotional health. Originally developed as a tool for service members to easily record and review their behavior changes, particularly after combat deployments, it has now become very popular with many civilian users around the world.

ACT Coach - http://t2health.dcoe.mil/apps/ACTCoach (iOS only)

A treatment-companion app for patients to use with their therapist while in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). Features include mindfulness exercises to practice the ACT core concepts, tools to help identify personal values and take concrete actions to live one's life by them, educational materials about ACT, logs to keep track of useful copying strategies.

Positive Activity Jackpot - http://t2health.dcoe.mil/apps/positiveactivityjackpot (Android only)

Uses a professional behavioral health therapy called pleasant event scheduling (PES), which is used to overcome depression and build resilience. This app features augmented reality technology to help users find nearby enjoyable activities and makes activity suggestions with local options and the ability to invite friends. Users can also "pull the lever" and let the app's jackpot function make the choice for them.

Anxiety and Stress Apps

Virtual Hope Box - http://t2health.dcoe.mil/apps/virtual-hope-box (iOS & Android)

Designed for use by patients and their behavioral health providers as an accessory to treatment. The VHB provides help with emotional regulation and coping with stress via personalized supportive audio, video, pictures, games, mindfulness exercises, positive messages and activity planning, inspirational quotes, coping statements, and other tools.

Moving Forward - www.veterantraining.va.gov/movingforward (iOS only)

Designed to help veterans and service members use stress management and problem solving tools on-the-go. It can be used alone, or in combination with the Moving Forward online course.

Breathe2Relax - http://t2health.dcoe.mil/apps/breathe2relax (iOS & Android)

A portable stress management too that includes hands-on diaphragmatic breathing exercises. Users can record their stress level on a 'visual analogue scale' by simply swiping a small bar to the left or to the right.

Tactical Breather - http://t2health.dcoe.mil/apps/tactical-breather (iOS & Android)

Used to gain control over physiological and psychological responses to stress. Through repetitive practice and training, users can learn to gain control of their heart rate, emotions, concentration, and other physiological and psychological responses to the body during stressful situations.

Mindfulness Coach - http://www.ptsd.va.gov/public/materials/apps/mobileapp_mindfulness_coach.asp (iOS only)

Designed to be used alone or as a part of treatment. Features include education about mindfulness, mindfulness exercises, strategies to help overcome challenges to mindfulness practice, log of mindfulness exercises to track progress, and reminders to support mindfulness practice.

Insomnia/Sleep Apps CBT-i Coach - https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/materials/apps/cbticoach_app_pro.asp (iOS & Android)

Designed for use by people who are participating in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-i) treatment. Features include: interactive sleep diary for daily logging of sleep habits; validated measure of insomnia severity, the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI); automatic calculation of the sleep prescription with therapist adjustment options; tools to improve sleep, including relaxation exercises; psychoeducation about sleep, healthy habits and CBT-I therapy; and customizable reminders to alert user to sleep hygiene, to record sleep habits, and to take sleep assessments.

Smoking/Tobacco Cessation Apps

Stay Quit Coach - www.mobile.va.gov/app/stay-quit-coach (iOS only)

Designed to help Veterans with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) quit smoking. It guides users in creating a tailored plan that takes into account their personal reasons for quitting. It provides information about smoking and quitting, interactive tools to help users cope with urges to smoke, and motivational messages and support contacts to help users stay smoke-free. This treatment is based on evidence-based clinical practices, and has been shown to double quit rates for Veterans with PTSD.

Weight management

MOVE! Coach - www.mobile.va.gov/app/move-coach (iOS only)

A weight loss app for Veterans, service members, their families, and others who want to lose weight. This 19-week program guides the participants to achieve success with weight loss through education, and use of tools, in an easy and convenient way. Participants can monitor, track, and receive feedback regarding their progress with weight, diet, and exercise goals.

Pain

WebMD Pain Coach - www.webmd.com/webmdpaincoachapp (iOS, & Android)

Allows patients to monitor and track their pain level on a scale of 1 to 10. They can also track triggers, treatment, mood, and more. Includes tips and goals organized into 5 lifestyle categories: food, rest, exercise, mood and treatments.

TBI/Concussion Concussion Coach - http://www.polytrauma.va.gov/ConcussionCoach.asp (iOS only)

For Veterans, Servicemembers, and others who have experienced a mild to moderate concussion. It provides portable tools to assess symptoms and to facilitate use of coping strategies.

mTBI Pocket Guide - http://t2health.dcoe.mil/apps/mtbi (iOS & Android)

For health care providers. Gives instant access to a comprehensive quick-reference guide on improving care for mTBI patients. Designed to reflect current clinical standards of care, it can help providers improve quality of care and clinical outcomes for patients. Use it to find information on assessing, treating, and managing common symptoms of mTBI patients. It offers clinicians a wide range of diagnostic, treatment and information resources.

Parenting

Parenting2Go - http://t2health.dcoe.mil/apps/Parenting2Go (iOS only)

Parenting2Go and the companion online course Parenting for Service Members and Veterans give military and veteran parents tools to help them reconnect with their families after a deployment and build closer relationships with their children anytime. It has five main components: A tool that helps parents shift gears between work and home in order to be more mentally "present" for their children; quick tips on topics related to reconnecting with families after a deployment; tools to help parents when they are feeling stressed or overwhelmed with parenting demands; an evidenced-based strategy that allows parents to count their positive and negative comments to their child; and access to a user's personal contacts and other resources to support their parenting efforts.

Biofeedback

BioZen - http://t2health.dcoe.mil/apps/biozen (Android only)

Can be paired with external sensors to provides users with live data covering a range of biophysiological signals, including electroencephalogram (EEG), electromyography (EMG), galvanic skin response (GSR), electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG), respiratory rate, and temperature.

Using BioZen requires compatible biosensor devices. BioZen can display several brain wave bands (Delta, Theta, Alpha, Beta, and Gamma) separately, as well as combinations of several bands using algorithms that may indicate relevant cognitive states, such as meditation and attention. BioZen features a meditation module that represents psychological information with user-selectable graphics that change in response to the user's biometric data. Biometric data is recorded in real time, so users can observe relationships between recorded biophysiological data and their thoughts and behavior. Users can create notes to document and categorize their recording session. BioZen automatically generates graphical feedback from the recording sessions to allow users to monitor their progress over time.

List of Past Trauma Psychology Newsletter Articles

Jacklynn M. Fitzgerald, Kaley Davis, Meghan Bennett, & Rachel Bollaert

Section Editor: Sydney Timmer-Murillo

Burden of Physical Health Comorbidities in the U.S. Veteran Population

Research on the efficacy of yoga to treat physical and mental health disorders is on the rise, although, to our knowledge, no review has yet summarized the effects of yoga in U.S. veterans. This review aims to summarize what is known regarding the feasibility and efficacy of yoga as a therapeutic in this population. Treating mental health disorders, notably posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders, remains a common focus in managing the health and well-being of U.S. veterans (Schnurr, 2022). While such focus is intuitive, approaches that narrowly focus on mental health alone may miss opportunities for improving life outcomes for veterans. This is because in addition to psychiatric disorders such as PTSD, U.S. veterans experience many physical health complications. Principal among these are obesity, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic syndromes (Ahmadi et al., 2011; Rosenbaum et al., 2015; van den Berk-Clark et al., 2018). Such physical comorbidities are not only linked to premature mortality (Franks & Olsson, 2007) and increased risk of hospital admissions (Chen et al., 2020), but also to greater PTSD severity (Babić, 2013; Heppner et al., 2012).

Notably, for U.S. Veterans, these physical health disorders are highly prevalent, as evidenced by the fact that over two-thirds of veterans with PTSD currently live with a metabolic syndrome, such as increased blood pressure, high blood sugar, or high cholesterol (Babić, 2013) and over 40% are classified as obese (Breland et al., 2017). Multiple factors may increase incidence of these disorders, foremost among them the fact that the U.S. veteran population is an aging demographic (Richard-Eaglin et al., 2020). For example, it is estimated that within the next three decades, over half of the U.S. veteran population will consist of individuals over the age of 60 (Richard-Eaglin et al., 2020). Although, age alone cannot fully account for prevalence of physical health disorders in this population (Assari, 2014), older aged Veterans in the health care system, particularly those with PTSD, will necessitate a more holistic approach to treatment and care. Here, it will be increasingly essential for care providers to jointly treat physical and mental health.

Exercise Trends and Barriers to Engagement

Alongside improved physical fitness, engagement of exercise is associated with reduction of early mortality, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity as evidenced in the general population (Chin et al., 2016; Colberg et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2022). Such reductions are apparent even when individuals engage in moderate levels of physical activity (Ekelund et al., 2019). Thus, engaging in different modalities and intensities of exercise may be a modifiable factor to decrease risk for negative health outcomes specific to the U.S. veteran population.

In recent years, exercise interventions have been employed as novel approaches for the treatment of mental health disorders, such as PTSD, in both community and military veteran populations, and results are promising (Hegberg et al., 2019a). In particular, a recent systematic review showed small-to-medium effects of exercise, including aerobic activity, strength-training, and yoga, on reducing PTSD symptoms in veterans (Reis, 2022) while other work shows exercise reduces PTSD symptoms when completed as a stand-alone regimen or as an adjunctive to standard psychological/pharmacological treatments (Hegberg et al., 2019b). Improved sleep quality and reduced waist circumference have also been reported in individuals with PTSD who undergo exercise, including resistance-training (Rosenbaum et al., 2015). Further, one study reported that female veterans with PTSD who underwent a 12-week exercise intervention consisting of moderate intensity aerobic exercise showed significant reductions in both PTSD and depressive symptoms (Shivakumar et al., 2017).

Despite the well-documented mental and physical health benefits associated with exercise in veterans, particularly those suffering from PTSD, the rates of physical inactivity remain high in this population. One study demonstrated that upwards of 68% of veterans with PTSD report no regular physical activity (Chwastiak et al., 2011). Low engagement in physical activity is likely due to significant barriers to engaging in exercise that exist for this population, including older age (Bollaert et al., 2023), a lack of clearance for engaging in exercise from a medical provider, and decreased social support (Hammarström et al., 2014; Metzgar et al., 2015; Venditti et al., 2014). Psychological barriers also exist. For instance, we have found decreased self-efficacy for overcoming barriers to exercise is related to less physical activity in U.S. veterans (Bollaert et al., 2023). However, these individuals retained a high motivation for engaging in exercise, despite reduced perceptions of self-efficacy (Bollaert et al., 2023). This suggests that strategies to strengthen individuals’ self-efficacy may be particularly helpful for this population, and that individuals who do not engage in physical activity still may be motivated to do so. One way to strengthen individuals’ self-efficacy may be through mastery experiences, whereby confidence develops after experiencing success in a particular task. Regarding exercise and yoga, interventionists could focus on highlighting individuals’ achievements, whether that be learning a new pose or continued attendance in a program. Another way to strengthen self-efficacy could be through verbal persuasion, or positive encouragement, either delivered from an interventionist or from one’s peers.

Yoga as a Promising Alternative

Prescribed exercise regimens may need to be specifically customized for U.S. veterans. Based on the above-mentioned barriers, activities that older veterans may find most difficult, such as high-intensity aerobic exercises, may be inadvisable for this population. Further, given the perceived social benefits associated with exercise in veterans (Holtz et al., 2014; Pebole & Hall, 2019), regimens that allow individuals to practice alongside others who may be able to offer social support and increase individual self-efficacy, whether that be other participants or exercise staff, may be particularly beneficial.

Yoga in particular is a form of exercise that has grown in popularity and accessibility in recent years and is associated with improved cardiovascular health (Cramer et al., 2014) and weight loss (Unick et al., 2022). Most importantly, yoga is a type of exercise that may be attractive to veterans precisely because it does not involve high intensity movement and can be conducted either

independently or in a group setting. Higher intensity or strength-based exercises may exacerbate physical discomfort, a particularly relevant consideration as the veteran population exhibits elevated medical comorbidities, including chronic pain that can develop as a direct result of injuries acquired during combat operations (Bayley et al., 2021). By contrast, yoga offers a low-impact alternative that is gaining increasing empirical support. Yoga is a mind-body exercise consisting of physical postures and stretching with a specific focus on breathing techniques and meditation (National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health., 2021). As an intervention, yoga has been associated with a variety of mental and physical health outcomes in the general population: reduced depressive symptoms (Cramer et al., 2013), stress (Riley & Park, 2015), and cardiovascular risk (Ernst & Lee, 2010), and improved well-being (Oken et al., 2006), self-compassion (Riley & Park, 2015), and sleep quality (Halpern et al., 2014).

Emerging evidence shows that yoga may be particularly beneficial for trauma-exposed individuals with resulting PTSD (Skaare, 2018; Wells et al., 2016). For example, individuals with PTSD who perform yoga experience reductions in symptoms (Seppälä et al., 2014), while a military-tailored, trauma-sensitive yoga intervention decreases PTSD severity in a clinically-meaningful way, based on PTSD score reduction as well as effect size for change (Cushing et al., 2018). In addition, yoga for veterans is associated with decreased insomnia, depression, and anxiety (Cushing et al., 2018) as well as substance use (Reddy et al., 2014). Recent research also demonstrates that yoga alleviates other physical symptoms in veterans specific to chronic pain (Bayley et al., 2021).

Considerations and Future Work

Despite such promise, relatively few empirical studies have been done to date examining the physiological and fitness effects of yoga in U.S. veterans, as well as assessing its feasibility in an aging U.S. veteran demographic. Specifically, there have been few (n = 3) randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on the use of yoga in a trauma-exposed population. One RCT found decreased PTSD symptoms after a 7-day breathing-based yoga intervention (Seppälä et al., 2014), while another found a decline in PTSD severity after 8 weeks of yoga (Jindani et al., 2015). A third RCT found a significant decline in PTSD symptoms after 10 weeks (van der Kolk et al., 2014) with effects sustained 1.5 years after the intervention in individuals who continued practicing (Rhodes et al., 2016). While these results are promising, yoga as a form of exercise targets both psychological and physiological health, while physiological changes as the result of long-term yoga have only been studied in other populations (Balaji et al., 2012) and have been left out in studies on yoga efficacy in veterans (Jindani et al., 2015; Seppälä et al., 2014; van der Kolk et al., 2014). To identify specific mechanisms of change for yoga as an exercise intervention, physiological measures – such as cardiovascular and respiratory fitness, muscular strength, and range of motion – are an important area of research on yoga efficacy. Further, because the target of yoga is theorized to act on the stress response system, any changes in psychological or physical health from yoga should be investigated through this lens. In addition, yoga as an intervention may need to be tailored in the veteran community to be trauma-specific and sensitive to the cardinal neurobiological symptoms of disorders, such as PTSD, which involves hyper-reactive arousal. Veterans with PTSD may feel particularly hesitant to partake in some aspects of yoga that may trigger stress responding. For example, yoga incorporates instructor-led corrections via touch that may activate high arousal. Indeed, qualitative research from those with chronic PTSD report having discomfort during sessions related to instructor-led touch specifically (Zaccari et al., 2020). Thus, better understanding of the neurobiology of PTSD may be instrumental to crafting a feasibility study tailored to this population.

Conclusion

The rising prevalence of comorbidities in the aging U.S. veteran population warrants continued research on alternative therapeutics for both physical and mental health, while the health benefits of engaging in physical activity are numerous and well-documented. Despite the high comorbidity between PTSD and physical health problems in U.S. veterans, these individuals experience significant barriers to engaging in exercise which is associated with lower physical activity levels. Yoga interventions offer a low-impact alternative to traditional aerobic exercise, making it an especially feasible option for aging veterans. Though yoga has been implicated in a range of positive outcomes related to mental and physical health, there is still much to be explored in terms of its use as a therapeutic intervention in military veterans.

JACKLYNN FITZGERALD, PhD, Assistant Professor of Psychology at Marquette University and Director of the Translational Affective Neuroscience Lab. Dr. Fitzgerald’s work is on the neurobiology of PTSD, including translational work in advancing our understanding of the neurobiological mechanisms of adjunctive therapies for PTSD, such as exercise and yoga.

KALEY DAVIS, Graduate Student in the Clinical Psychology doctoral program at Marquette University. Kaley’s work is on risk and resilience factors following trauma, such as investigating the role that health plays in posttraumatic growth.

MEGHAN BENNETT, Graduate Student in the Clinical Psychology doctoral program at Marquette University. Meghan’s work is on identifying neurobiological mechanisms of symptom remediation in PTSD in order to inform clinical interventions and treatment recommendations, such as the incorporation of exercise and yoga alongside psychotherapies.

RACHEL BOLLAERT, PhD, Clinical Assistant Professor of Exercise Science at Marquette University. Dr. Bollaert’s work focuses on the promotion of physical activity behavior for veterans and understanding behavioral and neurobiological associations with yoga, mindfulness, and PTSD.

Citation: Fitzgerald, J. M., Davis, K., Bennett, M., & Bollaert, R. (2023). Feasibility and efficacy of yoga as a therapeutic intervention for U.S. veterans. Trauma Psychology News, 18(1), 28-32. https://traumapsychnews.com

Dustin Lewis

Section Editor: Antonella Bariani

Peer Reviewers: Linda Zheng & Molly Becker

In August of 2022, I separated from the Air Force after nearly 11 years as an officer. I immediately transitioned into a master’s program in Counseling Psychology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, with the intention of working with veterans. The most recent United States Census Bureau data shows that there are approximately 18 million veterans in the United States, representing roughly 7% of the US population (Bureau, 2022). Military service members and veterans typically experience significant physical and psychological challenges. In the context of these challenges, veterans are at an increased risk of exposure to morally injurious events, which has been associated with an increased risk for suicidal behavior (Bryan et. al., 2014; Nichter et. al., 2021).

One of the many reasons why I started down the path of separating from the military and providing counseling to veterans was my own experience of moral injury and being surrounded by far too many suicides (one is more than enough). My decision to leave the military involved a lot of factors. One of them was the American withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021 and the moral injury that event imparted on me and many of my friends and peers.

The Department of Veteran’s Affairs (VA) describes moral injury as follows: “In traumatic or unusually stressful circumstances, people may perpetrate, fail to prevent, or witness events that contradict deeply held moral beliefs and expectations: (1) When someone does something that goes against their beliefs, this is often referred to as an act of commission, and when they fail to do something in line with their beliefs, that is often referred to as an act of omission. Individuals may also experience betrayal from leadership, others in positions of power or peers that can result in adverse outcomes. (2) Moral injury is the distressing psychological, behavioral, social, and sometimes spiritual aftermath of exposure to such events. (3) A moral injury can occur in response to acting or witnessing behaviors that go against an individual’s values and moral beliefs” (Norman & Maguen, 2020).

In my own words, moral injury occurs when you do something you do not want to do, in extreme circumstances where the only other options are also things you do not want to do. Often, moral injuries are defined by split-second decision making under demanding and unsettling circumstances (Barnes et. al., 2019).

Prior research has discussed the strong associations between exposure to morally injurious events and suicidal behavior (Bryan et. al., 2014; Nichter et. al., 2021; Wisco et. al., 2017). There are many challenges that follow experiencing these types of events. For me, moral injury, combined with PTSD, has manifested as stress, anxiety, depression, insomnia, and other intrusive experiences that are typically grouped under the general label of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). While symptoms of PTSD and moral injury often overlap and simultaneously exist, trauma research has noted distinct differences between the two (Barnes et. al., 2019). PTSD is typically conceptualized as a fear-based disorder, while moral injuries are based on the internal perception of a violation of one’s morals and often develops after the event has ended (Barnes et. al., 2019).

According to the United States Center for Disease Control (CDC), “Veterans bear a disproportionate but preventable burden.” Tragically, “out of the 130 suicides per day in 2019, 17 of those lives lost were veterans” (CDC, 2022, para. 3). Specifically, veteran suicide-related deaths have increased at a greater rate than those of the general U.S. population, with research demonstrating 36% and 30% increases in suicide rates respectively (CDC, 2023; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, n.d.).

Unfortunately, this is a reality that many veterans face as they navigate life after service. The majority of my time in the military was spent as a navigator on the AC-130 gunship, a heavily armed cargo airplane that has a rich and humbling history, and has been honed into a devastating tool of war. In my role as a navigator, my voice was one of the final pieces in a complex process of checks and balances that needed to be met before a bullet ever left our aircraft. During one of my many combat missions, my crew engaged a target that was a significant threat to the ground force that we were supporting. It was later confirmed that our target was valid and our engagement was justified. It was also confirmed that civilians, including women and children, were killed during this engagement. This was a moral injury to me. My effective use of the knowledge and skills that I had worked so long and hard to obtain had led me to contribute to the death of innocent civilians. This is a part of war and hearing that does not make it any easier to live with.

During the infamous withdrawal of American troops from Afghanistan in August of 2021, a friend of mine commanded a gunship crew flying over Kabul on August 16th. He watched from the sky as the events unfolded that led to the tragic takeoff of a C-17 aircraft laden with people holding onto the outside, clinging to any hope of escape (Cohen, 2022). My friend watched these events unfold with very little guidance on how he was expected to respond. He knew members of the crew flying that C-17 and had to grapple with the choice of watching a military aircraft overloaded with civilians crash and possibly kill everyone on board, or if he needed to command his crew to fire into the overwhelming mass of innocent people to prevent that. There’s no clear, simple answer for how to behave in that circumstance. And now my good friend and the rest of that crew are likely carrying that unique moral injury around every day. I watched the events in Kabul unfold from a hotel room on the first night of a two-week road trip, the day before I officially made my decision to separate from the military after contemplating the idea for over a year.

Living with moral injury is a unique and distinct experience. I do not have an answer for how to best address these issues and, for me, working through them is a daily occurrence. Going forward, future research is needed to better understand moral injury and its role in suicide prevention. My main concern in writing this article is that we have a current generation of veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan (myself included) who are being treated with outdated protocols. It is also particularly important for mental health researchers and providers alike to understand and distinguish the impact of moral injury on suicidal tendencies, within the context of interaction with PTSD. Finally, it is imperative that we all demonstrate grace and compassion to those around us, as many are carrying invisible burdens and experiences that we may never understand.

DUSTIN LEWIS is a first-year student in the two-year master’s in counseling psychology program at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. He is currently the Vice President of the Student Veterans of America chapter in Madison, WI. Dustin was born and raised in Eagle River, Wisconsin and received his bachelor’s in Psychology from UW–Madison in 2011. He then joined the Air Force and spent most of his career in the military as an AC-130U Navigator at Hurlburt Field, Florida.

Citation: Lewis, D. (2023). Suicide prevention in the context of moral injury and the Afghanistan withdrawal. Trauma Psychology News, 18(1), 34-36. https://traumapsychnews.com

Logan Pearson, Terri deRoon-Cassini, Mary E “Libby” Schroeder, & Daniel N. Holena

Section Editor: Sydney Timmer-Murillo

In the high-stakes environment of trauma care, the immediate treatment priorities must focus primarily on stabilizing physical injury. This often relegates concern for mental health to the backseat, where it unfortunately remains for much of the early period post-trauma. Despite the critical role that mental health plays in overall recovery and long-term outcomes, current literature suggests a gap in routine mental health assessment and intervention during the early stages of trauma care(deRoon-Cassini et al., 2019). This brief report focuses on the pervasiveness of psychopathology in recovery from traumatic injury via retrospective chart review.

We performed retrospective cohort analysis using a substantial data pool from 76 healthcare organizations on the TriNetX database and investigated the incidence and prevalence of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) diagnoses in the year following a traumatic injury, drawing comparisons between injured and non-injured patient cohorts. The findings revealed a notably higher incidence of depression, anxiety, and PTSD among individuals who endured a traumatic injury compared to those who did not. This disparity was particularly stark in the first month post-injury, where the incidence rates for depression, anxiety, and PTSD were 2.0, 2.0, and 1.8 times higher, respectively, among the injured cohort. This trend underscored the urgent need for early mental health assessments and interventions amidst the acute phase of trauma care, aligning with the recent American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma guidelines that emphasize early identification and intervention for mental health disorders to improve outcomes (American College of Surgeons Trauma Programs, 2022).

Beyond the immediate aftermath, we identified a sustained prevalence of these mental health disorders over the year following the traumatic event. The prevalence among the injured group stood at 26.3% for depression, 28.6% for anxiety, and 7.5% for PTSD, in stark contrast to the 15.3%, 18.6%, and 4.9%, respectively, in the non-injured group. This lingering impact of traumatic injuries on mental health accentuates the necessity for a comprehensive approach towards trauma care that extends well beyond the acute phase.

These disorders significantly impact recovery. Elevated depression scores are linked to higher pain levels at 1-month post-trauma, prolonged hospital stays, and reduced recovery odds at 12 months (Kellezi et al., 2017). PTSD strongly correlates with reduced health-related quality of life post-traumatic injury, while anxiety disorders correlate with increased postoperative mortality (Kiely et al., 2006; Geoffrion et al., 2021). Targeting these conditions in trauma recovery is promising, as multidisciplinary approaches encompassing psychological interventions have shown to lessen procedural complications and enhance patient quality of life both short and long term (Villa et al., 2020).

While our study’s results are compelling, relying on formal diagnoses to identify mental health conditions in a field still standardizing screening can lead to under-diagnosis. Similarly, using retrospective chart review hinges on the accuracy and completeness of pre-existing medical records, which may vary by organization.

Despite this, our comparative analysis highlighted a significant difference in mental health outcomes between injured and non-injured groups, underscoring the urgent need for standardized psychological assessments and interventions in trauma care. As awareness of how psychopathology affects recovery from traumatic injuries grows, it’s crucial to further explore and implement psychological supports to enhance the recovery journey of trauma survivors.

LOGAN PEARSON is a medical student at the Medical College of Wisconsin. His research interests include using innovative research methodologies to come up with creative solutions to community-identified needs. Following medical school, Logan plans to continue engaging in problem-solving endeavors.

TERRI DEROON-CASSINI, PhD, Professor, Division of Trauma & Acute Care Surgery, Dept of Surgery at MCW. She is the Exec Director of the Comprehensive Injury Center, focused on violence, suicide, and non-intentional injury prevention. She co-directs the gun violence prevention program at Froedtert Hospital, is co-Founder of the Milwaukee Trauma Outcomes Project, a research collaborative investigating trauma outcomes. She is a Licensed Psychologist and started the Trauma & Health Psychology Service for the FH/MCW trauma center and member of the multidisciplinary trauma quality of life clinic, providing integrative care for survivors of gun violence.

MARY E “LIBBY” SCHROEDER, MD is an Associate Professor of Surgery in the Division of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. Her research focuses on social determinants of health post-trauma as well as improving mental health outcomes in the setting of injury.

DANIEL N. HOLENA, MD is a professor of surgery and serves as director of research for the Division of Trauma and Acute care surgery. His research interests include trauma systems, the use of audiovisual recordings to improve processes of care in trauma resuscitation, and the application of the Failure to Rescue (FTR) metric to trauma populations. His research methods primarily focus on the use of large datasets and on abstraction of video recordings in the trauma setting.

Citation: Pearson, L., DeRoon-Cassini, T., Schroeder, S. E., & Holena, D. N. (2023).psychopathology following traumatic injury. Trauma Psychology News, 18(3), 22-24. https://traumapsychnews.com

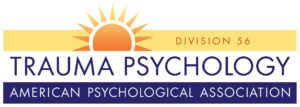

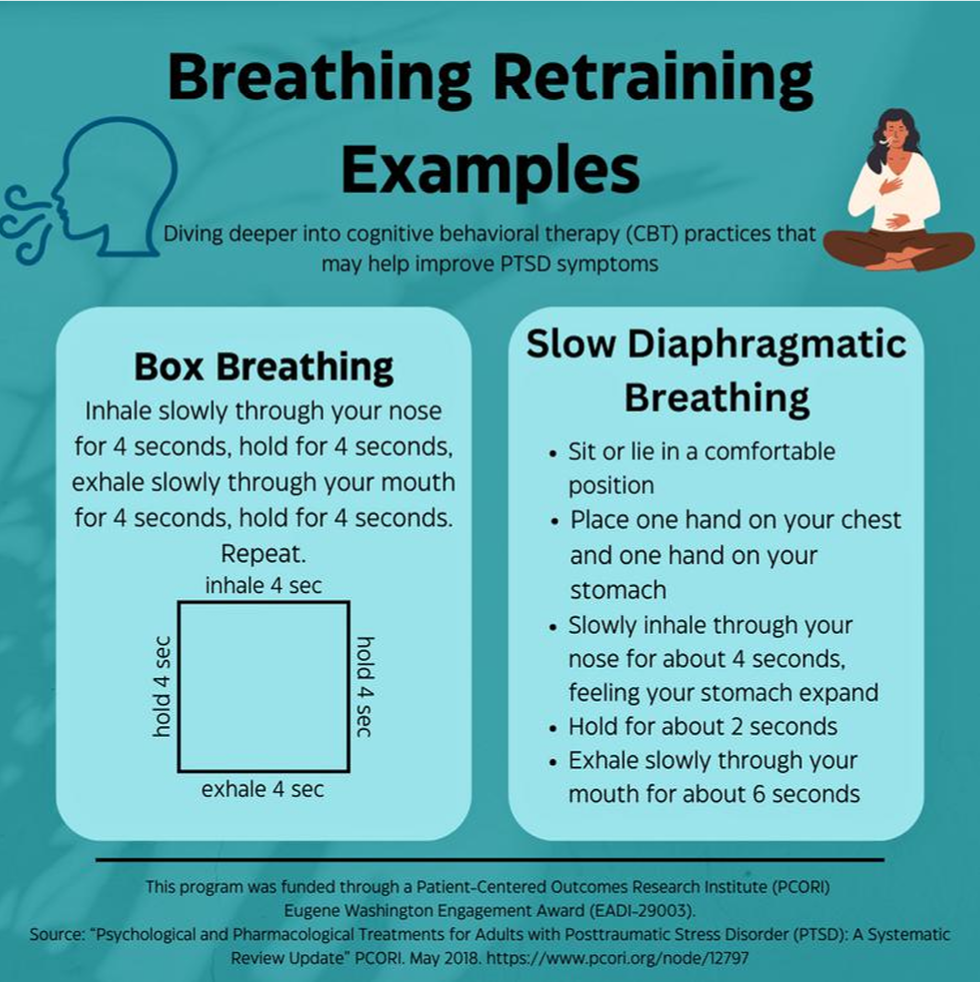

Infographics of Treatment Options for People with PTSD:

Created by Jacquelyn Baldwin, BSN, RN (Florida Atlantic University) and On The Double PCORI Dissemination Grant Team.

On The Double: A Veteran-Driven Dissemination Campaign Spreading Awareness of PTSD Treatment Options

Infographics of Treatment Options for People with PTSD

Teresa Granger

Section Editor

Created by Jacquelyn Baldwin, BSN, RN (Florida Atlantic University) and On The Double PCORI Dissemination Grant Team.

Distribution welcome.